Editor’s Note:We thank Dr. Yi Li for contributing this paper to www.ChinaUSFriendship.com; this paper is the full text of the morning speech on sociology given by Dr. Li on June 13, 2013, at Shandong University.

Ladies and gentlemen, good morning!

Thanks for giving me this opportunity to come to Shandong University (山东大学) to share some of my research findings. I would like to give my tribute to Mr. Lin Juren (林聚任). The sociology studies at Shandong University are an important effort in the sociology studies of East China. Mr. Lin Juren is the leader of sociology studies at today’s Shandong University. I give my tribute to Master Lin. Recently, China’ sociology has made great achievements. While enjoying these good results, we should not forget to be grateful and pay our respects to Mr. Fei Xiaotong (费孝通), Mr. Lu Xueyi (陆学艺) and Mr. Li Peilin (李培林) for leading this new era of Chinese sociology. Mr. Li Peilin is the distinguished alumnus of Shandong University.

It is my honor to once again come to Shandong. In 1986, I went up to Taishan (泰山), worshiped Qufu (translator’s note: 曲阜, the birth place of Confucius), and stayed in Qingdao (青岛)for a month. These days I visited Mt. Mengliang (孟良崮), the Hero Mountain (英雄山), the Thousand Buddha Mountain (千佛山), saw the Yellow River (黄河), the Daming Lake (大明湖), the Baotu Spring (趵突泉), and visited the Shandong Museum (山东博物馆). I could not help but think of a question: why was it the state of Qin (秦国) that unified the world rather than the state of Qi (齐国)? (translator’s note: Qi is one of the Zhou (周) vassal states of China, which existed from the Western Zhou Period (西周时期) until the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋时期) and the Warring States Period (战国时期). Qi’s boundaries are mainly located across Shandong Province, in the southeast of Hebei Province (河北省) and in the northeast of Henan Province (河南省). It was a big and powerful state, but was not able to unify China for various reasons).

In the recent two decades, the studies of the evolution of the structure of New China’s social stratification have made great achievements, both in theoretical and empirical aspects. In the theoretical studies, the spiraling progress made through negation of negation has gradually deepened our understanding. Indeed, before 1979, there was only class analysis, then this approach developed to negate the class analysis to focus only on the stratification analysis; in more recent years there was the negation of negation of the class analysis (Qiu Liping仇立平, 2006; Qiu Liping, 2007; Feng Shizheng冯仕政, 2008; Li Lulu 李路路et al., 2012) to emphasize both the class analysis and the stratification analysis. In empirical studies, the results have even been more fruitful (Li Tuo李拓, 2002; Lu Xueyi陆学艺, 2002; Zheng Hangsheng郑杭生, 2004; Li Peilin李培林, 2004; Qiu Zeqi邱泽奇, 2004; Wu Bo吴波, 2004; Li Chunling李春玲, 2005; Yang Jisheng扬继绳, 2006; Zhu Guanglei朱光磊, 2007;Li Yi李毅, 2008; Li Qiang李强, 2010; Liang Xiaosheng梁晓声, 2011). These scholars have achieved spectacular results on the evolution of New China’s structure of social stratification. They have taken a class analysis, or a stratification analysis, or a combination of the two, to make multi-faceted descriptive and analytical studies; their complementary talents and abilities have produced a perfect match.

However, in many empirical studies, the missing element is that among the numerous studies very few digital models reflect the comprehensive evolution of the structure of China's social stratification. The only existing two or three digital models merely reflect the static situation at some recent period of time instead of the history of evolution; they cannot intuitively grasp the macroscopic megatrend of the structure of New China’s social stratification over the latest sixty-some years. All the social structure and its evolution in the theoretical and empirical studies can finally be implemented by digital models. In the digital forms, it is easier to deepen theoretical perspectives and test empirical studies.

Today, I am going to present a brief overview of the Li Yi model of the Chinese social stratification. The Shandong University library has the Chinese versions of both my books The Structure and Evolution of Chinese Social Stratification (《中国社会分层的结构与演变》, 2008) and Introduction to Sociology (《社会学概论》, 2011). Some websites offer free dissemination of photocopies of these two books on the Internet. Since today’s lecture notes have already been passed to you, I can concentrate on the main points and make my speech shorter, leaving some time to listen to the criticisms and comments from the graduate students and professors here.

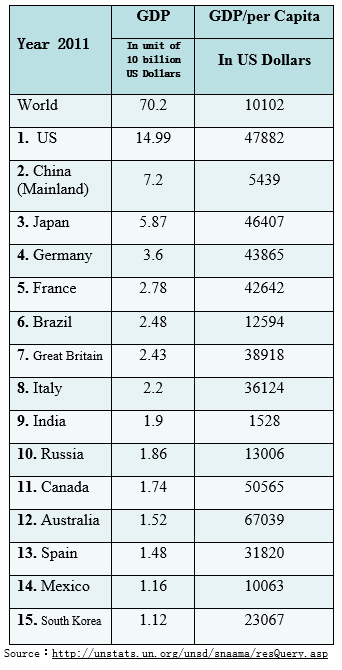

Before talking about the main topic, let us first take a look at the 2011 ranking of the gross domestic product (GDP) of world powers. Generally speaking, within another decade or so, China will surpass the U.S. GDP and return to the world number one ranking. Overall, before 1865 and after 2025, the history of human society is the history of China as the number one country in the world. The 160 years between 1865 and 2025, during which China being not the number one country in the world is just a brief interlude in the history of human society.

In addition, I would like to briefly introduce the English literature which studies the Chinese social stratification: see my book Introduction to Sociology (2011), page 99-103.

Also, here is a brief introduction of some important new trends in Western academia, see the American magazine The Foreign Affair Quarterly, volume 2, 2013.

1. Social stratification of China before 1949

We can study whether China has had or has not had a slave society, but this is not the topic today; we can study whether the Xia (夏) and Shang (商) Dynasties were or were not slave societies, but we are not going to talk about the social stratifications of Xia and Shang Dynasties today. Western Zhou was a feudal society, but we are not going to talk about its social stratification today. During the Spring and Autumn Period, and the Warring States Period, the Chinese feudal societies disintegrated. There were social stratifications in these periods, but we are not going to talk about them today. You can write five books about the social stratifications of the Xia, the Shang, the Western Zhou Dynasties, the Spring and Autumn Period, and the Warring States Period. The task will count on all of you, the graduate students, here.

The Chinese society from the Qin Dynasty to the Qing (清) Dynasty was not a feudal society. China ended the feudal society nearly two thousand years earlier than Europe, which is the important reason for China being more advanced than the rest of the world for nearly two thousand years. From the Qin Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty, the Chinese society was not feudal. But what kind of society was it then? The Chinese academic research on this topic is still far from adequate. The social stratifications of the Qin, the Han (汉), the Sui (隋), the Tang (唐), the Song (宋), the Yuan (元), the Ming (明) and the Qing Dynasties can be written in eight books, and we are counting on all of you, the graduate students, here.

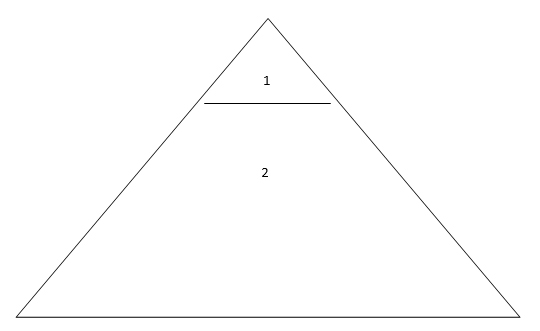

From the Qin Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty the general description of their social stratification is a pyramid-shaped figure. According to the English edition of The Cambridge History of China (《剑桥中国史》), Volume 13, Page 30, I show a pyramid in Figure 2-1 of my book. The upper ruling class consisted of the royal families, the government officials, the people who made great achievements, the landlords, the merchants and the exam candidates, accounting for approximately 5 percent of the population. The lower class being ruled consisted of the farmers, the artisans and the small businessmen, accounting for approximately 95 percent of the population. When officials had money, they could buy land and became landowners. If big merchants saved enough money, they could also buy land and become landowners. The officials, the landowners and the businessmen could work hard to develop their next generations to take the imperial examination to strive for becoming officials, or spend money to buy fame. Thus, the three categories of the ruling class could be connected together. However, there was also the phenomenon that it took only three generations to go from clogs to clogs. Whereas the lower class people, through regime change, imperial examination, money saved from business, and land purchase, could also have some small possibility to move up the social ladder into the upper class. This extremely limited openness and mobility were the prominent manifestation and highlights of the advanced system of social stratification from the Qin to the Qing Dynasties of China. They are the important reasons why the Chinese society could have led the world for nearly two thousand years.

Note: 1. The royal families, the government officials, the people who made great achievements, the landlords, the big merchants and the exam candidates accounted for 5 percent of the population.

2. The farmers, the artisans and the small businessmen accounted for 95 percent of the population.

Source: English edition of The Cambridge History of China, Volume 13, Page 30.

From 1840 to 1949, little change occurred in the lower class. The peasantry and the artisans did not experience much change. A new modern working class emerged, but was very weak. Until 1949, the Chinese working class was just slightly more than 3 million people. Among the five hundred million Chinese people, only about 3 million were workers; this is an unimaginably small number. Besides, the majority of the workers were female and child laborers; and the majority of workers were concentrated in the two sectors of silk farming and flour industries.

The upper class varied greatly. In addition to the control of China by the Western powers, the new upper class consisted of the military leaders, the new intellectuals, the national capitalists, the landowners, and the technical bureaucrats. My book has analyzed all five categories and especially focused on the analysis of China’s cadre system before 1949. The social stratification of China after 1949 has evolved from such a structure.

2. Social stratification of China 1949-1959

I think that over the sixty years since the founding of the country, the first thirty years and the later thirty years all had brilliant achievements as well as serious errors. During the first thirty years, both the achievements and the mistakes were larger than during the later thirty years. The Rightists think that the first thirty years made no achievement or very small achievements. This is wrong. The Leftists believe that the later thirty years made no achievement or very small achievements. This is also wrong. The Rightists think that the first thirty years made too large mistakes and the first thirty years should be negated. This is wrong. The Leftists believe that the later thirty years made too large mistakes and the later thirty years should be denied. This is also wrong.

The years from 1949 to 1976 can be called the Mao era. Recently, the Guangming Daily (《光明日报》) published a speech given on January 5, 2013, by the Chairman of the State Central Military Commission Xi Jinping (习近平). Xi said that denying Mao Zedong (毛泽东) would create a state of chaos. Last year, the report at the 18th Party Congress once again evaluated the Mao era. It reads as follows: "The Party's first generation of central collective leadership with Comrade Mao Zedong at the core led the whole Party and the people of all ethnic groups in China in completing the new-democratic revolution, carrying out socialist transformation and establishing the basic system of socialism, thereby accomplishing the most profound and the greatest social transformation in China’s history. This created the fundamental political prerequisite and systemic foundation for all the development and progress in contemporary China. In the course of socialist development, the Party developed distinctively creative theories and achieved tremendous successes despite serious setbacks, thus providing invaluable experience as well as a theoretical and material basis for launching the great initiative of building socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new historical period." Here, the sentence "accomplishing the most profound and the greatest social transformation in China's history” is true from the perspective of the evolution of the structure of the social stratification.

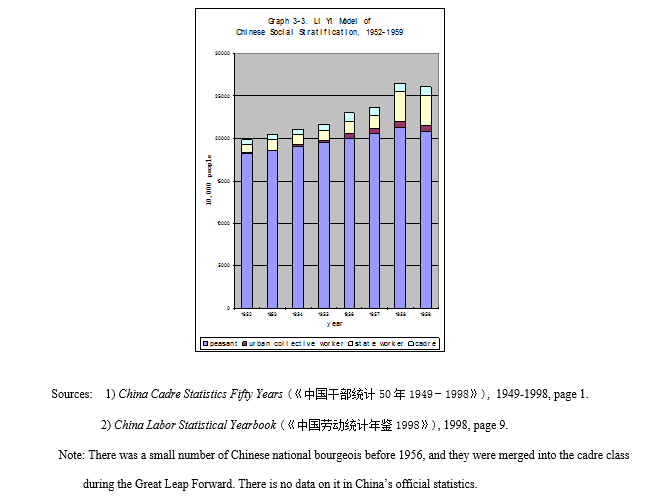

In just a few years, the New China formed three large blocks of structure of social stratification composed of a peasant class, a working class and cadres, see Figure 3-3. Through land reform, the landlord class which had existed for over two thousand years was eliminated. The mainstream academia of America, Japan and Europe basically has recognized China's land reform. But in recent years, some Chinese scholars began to deny land reform. From the viewpoint of Development Sociology, land reform is essential and indispensable for the establishment of a modern industrial power. For the situation regarding land reform, see Luo Pinghan’s book The History of Land Reform Campaign (罗平汉《土地改革运动史》,2005). For international comparative studies, see Tan Chongtai’s Comparative Studies of Early Development Stages of Developed Economics and Current Economic Developments of Developing Economics (谭崇台《发达国家发展初期与当今发展中国家经济发展比较研究》, 2008). The national bourgeoisie was eliminated through public-private partnerships and buy-outs. People beat drums and struck gongs in the day time to show support, but cried at night. It now appears that eliminating all the private restaurants, bathhouses, barber shops and small workshops was negative to the social and economic development.

Overall, this new structure of social stratification "accomplished the most profound and the greatest social transformation in Chinese history", mobilized the enthusiasm of workers, peasants and soldiers, who were the majority of the population, and laid a solid social foundation for the New China. For example, China participated in the war to resist U.S. and aided North Korea during the Mao Zedong era, established a complete industrial system, independently developed atomic and hydrogen bombs and man-made satellites, defeated India in the 1962 India border war against China, engaged in the Three-line Constructions (they were large-scale defense, science and technology, industry and transport infrastructure constructions in three frontiers of China started from 1964), initiated the oil campaign in Daqing (大庆) in 1964, built the Chengdu-Kunming Railway (成昆铁路)between 1958 and 1970, completed the Red Flag Canal (红旗渠) in 1965, aided Vietnam to resist the U.S. in the 1960s, joined the Third World to fight against the U.S. hegemony, supported the Third World, formed the triangular relationship between the U.S., the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and China, and extended the Chinese average life expectancy from 35 years to 68 years.

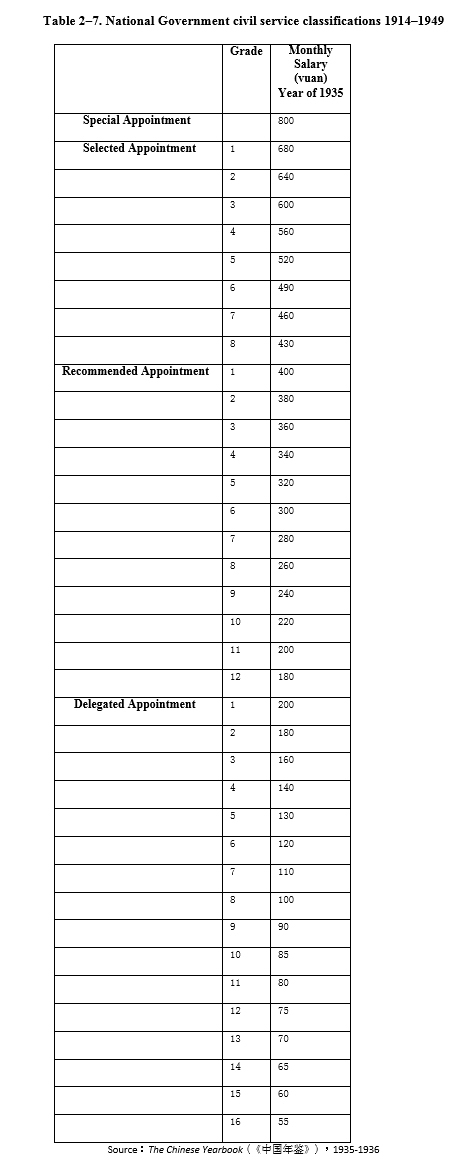

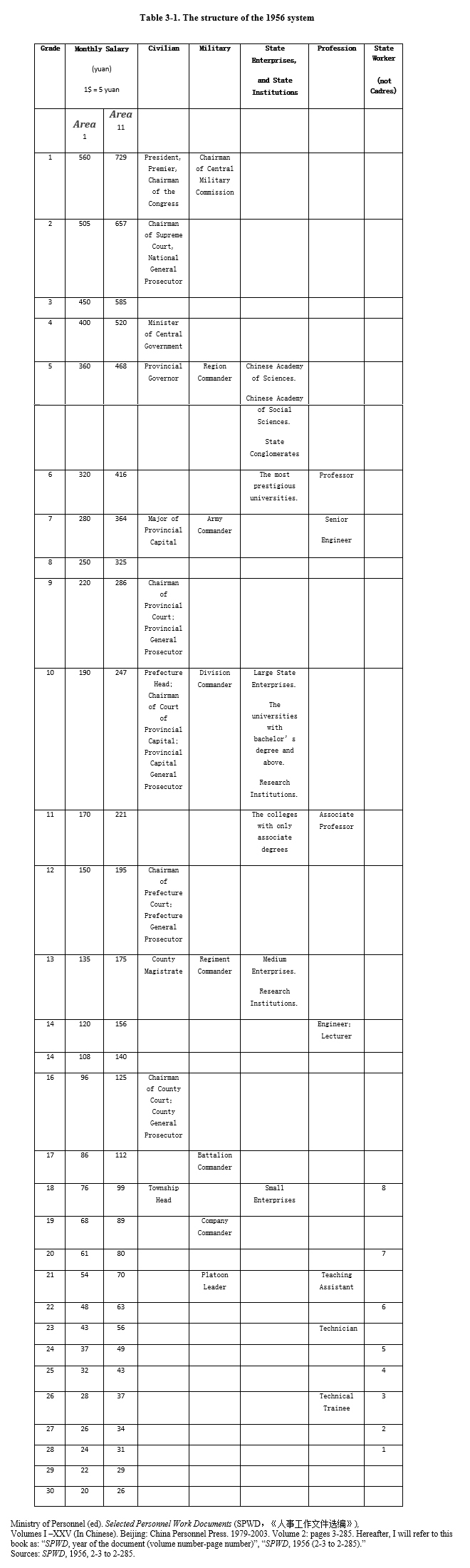

But Mao Zedong was also discontent with this new structure. Take the college entrance examination as an example. In 1905 China abolished the imperial examination, but from 1952 to 1955, China restored the imperial examination in the name of college entrance examination. Who made the decision? Till this day, I still have not found the answer. Mao Zedong did not seem to know the matter of restoring the college entrance examination. I suspect that the decision was probably made with the participation of Liu Shaoqi (刘少奇), Zhou Enlai (周恩来) and Deng Xiaoping (邓小平). Later I shall mention that Mao’s disapproval of the entrance examination was one of the important reasons for his launch of the Cultural Revolution. Another example concerns the wages. Comparing Table 3-1 with Table 2-7, you can see that the New China wage gaps were even larger than those of the Republic of China. Mao Zedong, of course, was very unhappy about it, which later also became an important reason for Mao to launch the Cultural Revolution.

In 1958 the residence permit (户口hukou) system which separated the urban and rural areas was established. From the information I could gather, I have not found that Mao knew this matter. According to the existing literature we can speculate that in addition to Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping might also have been involved in the decision-making. From discussions shown below you can see that during the Cultural Revolution, the youth rustication movement (the movement of educated Chinese urban youth going and working in the countryside and mountain areas) and the May 7 Cadre School (forcing educated people into re-education and peasant labor) initiated by Mao Zedong all aimed at eliminating the three major differences, especially the urban-rural isolation.

3. Social stratification of China 1959-1979

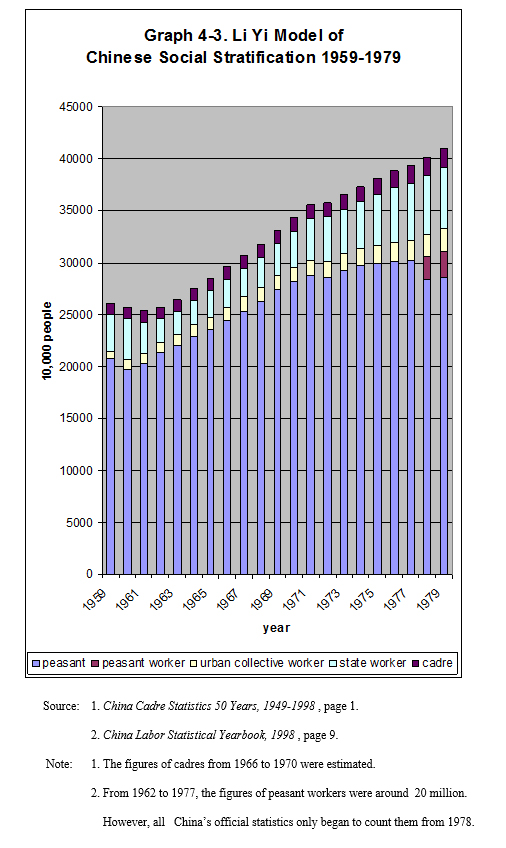

Figure 4-3 shows the structure and evolution of China’s social stratification during these two decades. There were almost no major changes in the three large structures composed of cadres, workers and peasants. If there was any change, it was the slow growth in the proportion of workers. The influence of the ten-year Cultural Revolution on the structure of China's social stratification seen in Figure 4-3 was very limited. Why? It will become very clear after we recall the relevant policies of the Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution abolished the college entrance examination and replaced the university students by students who had worker, peasant or soldier background, or the so-called worker-peasant-soldier students. In the fifties, after restoring the imperial examination in the name of the college entrance examination, in 1957, 80 percent of the university students in the countryside came from families of landlords, rich peasants and capitalists. Mao Zedong was extremely unhappy with this situation. In 1966, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, a major policy was to cancel the college entrance examination. In 1972, the universities restored their admission system by recruiting from the worker-peasant-soldier students through recommendation. From 1972 to 1976, there were a total of 820,000 worker-peasant-soldier students. Now, among the central and provincial leaders, there are a number of worker-peasant-soldier students including the chairman of the Central Military Commission Xi Jinping. From Table 7-1, we can see that in 1964, 1982 and 1990, the ratio of the mainland college or above degree population was 0.4 percent, 0.6 percent and 1.4 percent, respectively. In other words, after the abolition of the college entrance examination (1966), the direct impact on the Chinese college or above degree population was at most 1 percent (from 0.4 percent to 0.6 and 1.4 percent, respectively).

During the decade of the Cultural Revolution, these 820,000 worker-peasant-soldier students and 410,000 demobilized cadres could not meet the needs of social and economic development. Therefore, 4.45 million workers took titles as officials and a few million peasants took jobs as cadres. After Deng Xiaoping ended the Cultural Revolution, the peasants who took the jobs as cadres were asked to return to their homes to do farming work again; a million of the workers who took titles as officials were laid off; and others, through five different kinds of part-time diploma or other methods, eventually became the official national cadres. China then had a population of 700 million; adding the number of workers who worked as officials and peasants who worked as cadres, the total was less than 10 million. The impact was limited.

During the decade of the Cultural Revolution, about 80 million high school and junior high school graduates went to the countryside to work as farmers. Of these, nearly 60 million were originally farmers; they were called the educated youth returning to their hometowns. So, there were more than 20 million junior high school and high school graduates from the cities going to work in the countryside and mountain areas with an average of six years working as farmers. Afterwards, the vast majority of them went back to the cities. For more than a decade, the American and Chinese academic circles have had heated debates on the issue of going to work in the countryside and mountain areas. One school of thought is that the period of educated youths going to work in the countryside was a dark episode. Another school of thought argues that those were days of burning passion with pros and cons, and a considerable fraction of the educated youth got a rare training. The two sides sometimes get very emotional. Now, the Central Military Commission Chairman Xi Jinping, the Prime Minister Li Keqiang (李克强), and a large number of national and provincial leaders have backgrounds as educated youths. According to my observation, among these educated youths, few have rejected entirely their years as educated youths. At that time China had seven to eight hundred million people, so the impact of barely more than 20 million urban educated youths who went to the countryside and then returned to the cities to the structure of the social stratification, no matter how stressed, was very limited. If, during the past two decades, the Cultural Revolution and other events had a limited impact to the structure of China’s social stratification, then what event has had a significant impact on it?

I personally think that it was the Three-line Constructions (三线建设). During these twenty years (1959-1979), China was largely in a quasi-state of war. On April 25, 1964, the report of the General Staff to Chairman Mao and the Party Central Committee described the serious consequences of a preemptive surprise attack against Chinese coastal cities by the United States or the Soviet Union. At that time, 50 percent of China’s civilian industry and 52 percent of its military industry were concentrated in the 14 metropolises with population over one million, which had no reliable air-defense capability. Early in a war, the enemies could paralyze China's major railways, bridges, ports, and no big dam could avoid bursting. After four months of consideration, on the next day after the United States launched the Gulf of Tonkin Incident (translator’s note: 东京湾事件,a series of military clashes that took place in the Gulf of Tonkin between the U.S. and North Vietnam on August 2-4, 1964; after that the U.S. decided to escalate the Vietnam War), Mao Zedong made the final decision to begin the Three-line Constructions. In the first-tier (front line) areas, all new construction projects including factories, research institutes and universities were stopped, not to mention urban constructions. All the important factories, research institutes and universities in the first- and second-tier areas were dispersed to the third-tier areas to be close to the mountains or even directly inside a large cave. From 1965 to 1985, in order to be combat ready, China’s fixed asset investments shifted from the front line areas to the third-tier areas and basically stopped the development of urbanization such as large reservoirs like the Three Gorges Dam. The stagnation of urbanization also directly slowed down China's industrialization process. Because of the war preparation and the Three-line Constructions, the progress of rural urbanization and transforming farmers into workers before 1985 was very slow. Since 1840, China was confronted with repeated foreign aggressions and suffered the Centennial National Humiliation. In order to avoid the risk of being further trampled, the nation must carry out the Three-line Constructions and made the huge sacrifice of delaying rural urbanization and transforming farmers into workers. As Mao wrote in his 1962 poem: “Only with great ambition and the willingness of making sacrifices, can we wake the sun and moon to give us a new day” (唯有牺牲多壮志,敢教日月换新天).

|