Editor's note: This article is taken from a chapter of the book Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation written by Professor Min Zhou. We thank her for giving us the permission to publish it on www.ChinaUSFriendship.com.

Demographic Trends and Characteristics of Contemporary Chinese America1

Outside Asia, the United States has largest ethnic Chinese population. Chinese Americans are also the oldest and largest Asian origin group in the United States. They have endured a long history of migration and settlement that dates back to the late 1840s, including more than 60 years of legal exclusion. With the lifting of legal barriers to Chinese immigration after World War II and the enactment of a series of liberal immigration legislation since the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965 (also called the Hart-Celler Act of 1965), the Chinese American community has increased 13 times: from 237,000 in 1960, to 1.6 million in 1990, and to 3.6 million in 2006 (including nearly half a million mixed-race persons) by the official census count.2 Much of this tremendous growth is primarily due to post-1965 immigration. According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, nearly 1.8 million immigrants were admitted to the United States from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan as permanent residents between 1960 and 2006, more than four times of sum total admitted from 1850-1959.3 China has been on the USCIS’ list of top ten immigrant-origin countries in the United States since 1980. The U.S. Census also attests to the big part played by immigration. As of 2006, foreign born Chinese accounted for nearly two-thirds of the Chinese American population, more than half (56%) of the foreign born arrived after 1990, and 59 percent of the foreign born were naturalized U.S. citizens.4 What is the current state of Chinese America? This chapter offers a demographic profile of Chinese Americans and discusses some of the important implications of drastic demographic changes for community development in the United States.

A Historical Look at Demographic Trends

The Chinese American community has remained an immigrant-dominant community, even though this ethnic group arrived in the United States at a much earlier time than many Southern and Eastern European-origin groups and than any other Asian-origin groups. While the majority of Italian, Jewish, and Japanese Americans are maturing into third and fourth-plus generations upon their respective groups’ first arrival in the United States, Chinese Americans at the dawn of the 21st century are primarily made up of the first generation (foreign born, 63%) and second generation (U.S. born of foreign born parentage, 27%). The third generation (U.S. born of U.S. born parentage) accounts for only 10 percent.

Legal exclusion that lasted for more than 60 years between 1882 and 1943 largely explains the stifled natural population growth prior to World War II, and post-1965 immigration policies the surge of Chinese immigration. In the mid-19th century, most Chinese immigrants came to Hawaii and the U.S. mainland as contract labor, working at first in the plantation economy in Hawaii and in the mining industry on the West Coast and later on the transcontinental railroads west of the Rocky Mountains. These earlier immigrants were almost entirely from the Guangzhou (Canton) region of South China and most intended to “sojourn” for only a short time and return home with “gold” and glory.5 But few had much luck in the gold mountain (referring to America); many found themselves with little gold but plenty of unjust treatment and exclusion. In the 1870s, white workers’ frustration with economic distress, labor market uncertainty, and capitalist exploitation turned into anti-Chinese sentiment and racist attacks against the Chinese. Whites accused the Chinese of building “a filthy nest of iniquity and rottenness” in the midst of the American society and driving away white labor by “stealthy” competition and called the Chinese the “yellow peril,” the “Chinese menace,” and the “indispensable enemy.”6 In 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was renewed in 1892 and later extended to exclude all Asian immigrants until World War II.

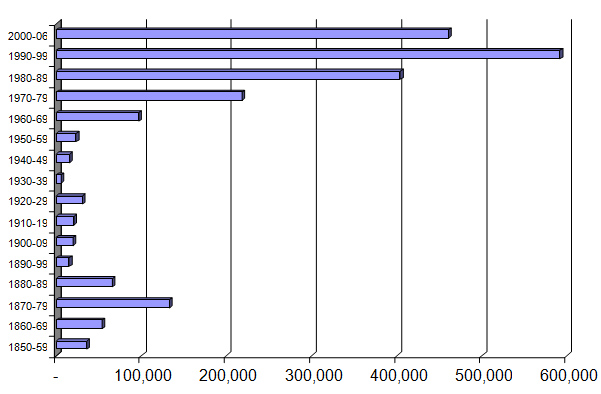

Legal exclusion, augmented by extralegal persecution and anti-Chinese violence, effectively drove the Chinese out of the mines, farms, woolen mills, and factories and forced them to cluster in urban enclaves on the West Coast that would evolve into Chinatowns.7 As a result, many Chinese laborers already in the United States lost hope of ever fulfilling their dreams and returned permanently to China. Others, who could not afford the return journey (either because they had no money for the trip or because they felt ashamed to return home penniless), gravitated toward San Francisco’s Chinatown for self-protection.8 Still others traveled eastward to look for alternative means of livelihood. The number of new immigrants arriving in the United States from China dwindled from 123,000 in the 1870s to 14,800 in the 1890s, and then to a historically low number of 5,000 in the 1930s. This trend did not change significantly until the 1960s—two decades after Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Chinese Immigrants Admitted to the United States 1850-2006

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2007, table 2, see http://www.dhs.gov/ximgtn/statistics/publications/LPR07.shtm.

Chinatowns in the Northeast, particularly New York, and the mid-West, particularly Chicago, grew to absorb those fleeing the extreme persecution in California.9 Consequently, the proportion of Chinese living in California decreased in the first half of the 20th century, and the ethnic Chinese population grew slowly with a gradual relaxation of the severely skewed sex ratio. As Table 2.1 illustrates, the ethnic Chinese population growth rate faced ups and downs by decade, but basically remained stagnant in the span of half a century from 1890 to 1940. The sex ratio for Chinese was 2,679 males per 100 females in 1890 and dropped steadily over time, but males still outnumbered females by more than 2:1 by the 1940s.

Table 2.1: Chinese American Population: Number, Sex Ratio, Nativity, and State of Residence, 1890-2000

|

Year |

Number |

Sex Ratio

(Males per 100 females) |

Percent

U.S. Born |

Percent

in California |

|

1890 |

107,475 |

2,679 |

.7 |

67.4 |

|

1900 |

118,746 |

1,385 |

9.3 |

38.5 |

|

1910 |

94,414 |

926 |

20.7 |

38.4 |

|

1920 |

85,202 |

466 |

30.1 |

33.8 |

|

1930 |

102,159 |

296 |

41.2 |

36.6 |

|

1940 |

106,334 |

224 |

51.9 |

37.2 |

|

1950 |

150,005 |

168 |

53.0 |

38.9 |

|

1960 |

237,292 |

133 |

60.5 |

40.3 |

|

1970 |

435,062 |

110 |

53.1 |

39.1 |

|

1980 |

812,178 |

102 |

36.7 |

40.1 |

|

1990 |

1,645,472 |

99 |

30.7 |

42.9 |

|

2000 |

2,879,636 |

94 |

31.0 |

40.0 |

|

2006* |

3,565,458 |

93 |

37.0 |

-- |

Source: U.S. Census of the Population 1890-2000.

* 2006 American Community Survey.

The shortage of women combined with the “paper son” phenomenon and the illegal entry of male laborers during exclusion era distorted the natural development of the Chinese American family.10 In 1900, less than nine percent of the Chinese American population was U.S. born. Since then, the share of the U.S. born increased significantly in each of the succeeding decade until 1960 as affected by the Chinese Exclusion Act. Accordingly, the proportion of children under 14 years of age increased substantially from a low of 3.4 percent in 1900 to a high of 33 percent in 1960. After the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, more women than men were admitted to the United States, mostly as war brides, but the annual quota of immigrant visas for the Chinese had remained 105 for the next two decades.11 At the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, hundreds of refugees and their families fled the Communist regime and arrived in the United States either directly from China or via Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other countries in the early 1950s.

These demographic trends led to the birth of a visible second and third generation between the 1940s and 1960s, during which the U.S. born outnumbered the foreign born population (see Table 2.1). In 1960, more than 60 percent of the Chinese American population was U.S. born. However, the absolute number of the U.S. born population was relatively small and much younger (a third was under age 14) than the average U.S. population.12 In 2006, the proportion of U.S. born dropped to 37 percent. Even today, members of both second and third generations are still very young and have not yet come of age in significant numbers compared to the first generation. The 2000 U.S. Current Population Survey indicates that in the second generation, 44 percent of Chinese Americans are between ages 0-17 and 10 percent between ages 18-24, compared to eight percent and eight percent, respectively in the first generation.

Intra-Group Diversity

In much of the pre-World-War-II era, the Chinese American community was essentially an isolated bachelor society consisting of a small merchant class and a vast working class of sojourners whose homeland was mainland China and whose lives were oriented toward an eventual return to that homeland. During that time, most of Chinese immigrants were from villages of the Si Yi (Sze Yap) region, speaking Taishanese (a local dialect incomprehensible even to the Cantonese), and the Pearl River Delta area in the greater Canton region, including San Yi (Sam Yap).13 Most left their families behind in China and came to America as sojourners with the aim of making a “gold” fortune and returning home. And most were poor and uneducated and had to work at odd jobs that few Americans wanted. Laundrymen, cooks or waiters, and household servants characterized most of the workers in Chinatown. Furthermore, they spoke very little English and seemed unassimilated in the eyes of Americans. As “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” the Chinese were not allowed to naturalize.

Since World War II, and particularly since the enactment of the Hart-Celler Act of 1965, the ethnic community has experienced unprecedented demographic and social transformation from a bachelor society to a family community. The 13-fold growth of the Chinese American population from 1960 to 2006 is not merely a matter of quantitative change but marks a turning point in community transformation. What characterizes this significant development is the tremendous intra-group diversity in terms of places of origin, socioeconomic backgrounds, patterns of geographic settlement, and trajectories of social mobility.

Compared to their earlier counterparts, contemporary Chinese immigrants have arrived not only from Mainland China but also from the greater Chinese Diaspora—Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, the Americas, and other parts of the world. In Los Angeles, for example, 23 percent of Chinese American population was born in the United States, 27 percent in mainland China, 20 percent in Taiwan, eight percent in Hong Kong, and 22 percent in other countries around the world as of 1990. Linguistically, Chinese immigrants come from a much wider variety of dialect groups than in the past. For example, all ethnic Chinese share a single ancestral written language (varied only in traditional and simplified versions of characters), but speak numerous regional dialects—Mandarin, Cantonese, Fujianese, Hakka, Chaozhounese, and Shanghainese—that are not easily understood within the group. About 83 percent of Chinese Americans speak Chinese, or a Chinese dialect at home. In the United States today, Chinese is the second largest foreign language spoken at home (by 2.3 million people), next only to Spanish.14

Contemporary Chinese immigrants have also come from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Some arrived in the U.S. with little money, minimum education, and few job skills, which forced them to take low-wage jobs and settle in deteriorating urban neighborhoods. Others came with family savings, education and skills far above the levels of average Americans. Nationwide, levels of educational achievement among Chinese Americans are significantly higher than those of the general U.S. population since 1980. The 2004 American Community Survey reports that half of adult Chinese Americans (25 years or older) have attained four or more years of college education, compared to 30 percent of non-Hispanic whites. Immigrants from Taiwan displayed the highest levels of educational attainment with nearly two-thirds completing at least four years of college, followed by those from Hong Kong (just shy of 50%) and from the Mainland (about a third). Professional occupations were also more common among Chinese American workers (16 years or older) than among non-Hispanic white workers (52% vs. 38%). The annual median household incomes for Chinese Americans were $57,000 in 2003 dollars, compared to $49,000 for non-Hispanic whites. While major socioeconomic indicators are above the national average and above those of non-Hispanic whites, the poverty rate for Chinese Americans was higher (13%), compared to nine percent for non-Hispanic whites; and homeownership rate for Chinese was lower (63%), compared to 74 percent for non-Hispanic whites.15

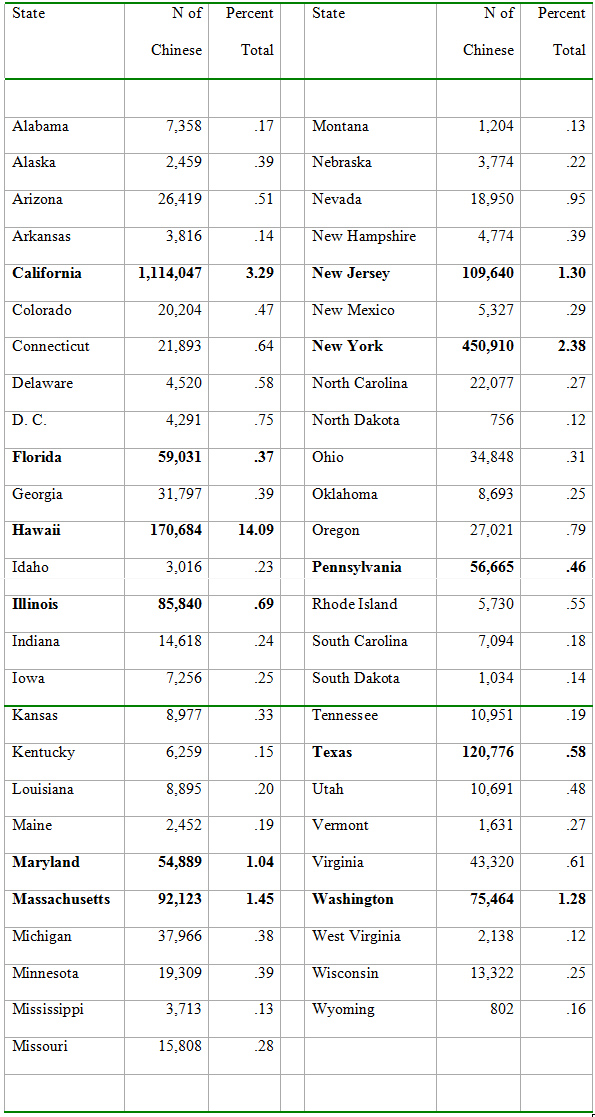

The settlement patterns of Chinese Americans at the dawn of the 21st century are characterized by concentration as well as dispersion. Geographical concentration, to some extent, follows a historical pattern: Chinese Americans continue to concentrate in the West and in urban areas. This traditional pattern of regional concentration continues to hold. For example, over half of the ethnic Chinese population was concentrated in just three metropolitan regions—New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.16 Table 2.2 provides descriptive statistics of the Chinese American population by state. As of 2000, one state, California, by itself accounted for 40 percent of all Chinese Americans (1.1 million); New York accounted for 16 percent, second only to California, and Hawaii for six percent. However, other states that historically received fewer Chinese immigrants witnessed phenomenal growth, such as Texas, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Illinois, Washington, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Maryland. Among cities with populations over 100,000, New York City (365,000), San Francisco city (161,000), Los Angeles city (74,000), Honolulu city (69,000), and San Jose city (58,000) have the largest numbers of Chinese Americans.

Table 2.2 Chinese American Population by State, 2000

Source: U.S. Census of the Population, 2000. Online access on September 7, 2007: http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html?_lang=en/.

Within each of these metropolitan regions, however, the settlement pattern tends to be bi-modal where ethnic concentration and dispersion are equally significant. Traditional urban enclaves, such as Chinatowns in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Boston, have continued to exist and receive new immigrants, but they no longer serve as primary centers of initial settlement for many new immigrants, especially members of the educated and professional middle-class who are bypassing inner cities to settle into suburbs immediately after arrival.17 Currently, only 14 percent of the Chinese in New York, eight percent of the Chinese in San Francisco, and less than three percent the Chinese in Los Angeles live in old Chinatowns. The majority of the Chinese American population is spreading out in outer areas or suburbs in traditional gateway cities as well as in new urban centers of Asian settlement across the country, and half of all Chinese Americans live in suburbs. Mandarin-speaking co-ethnics from mainland China, those from Taiwan, and those of higher socioeconomic status tend to stay away from Cantonese-dominant old Chinatowns. Once settled, they tend to establish new ethnic communities, often in more affluent urban neighborhoods and suburbs, such as the “second Chinatown” in Flushing, New York, and “Little Taipei” in Monterey Park, California.18 As a result of the tremendous influx of contemporary Chinese immigrants, old Chinatowns in the United States are being transformed in ways unimaginable in the past. The Chinatown as a transplanted village of shared origins and culture has evolved into a full-fledged family-based community with a new cosmopolitan vibrancy transcending territorial and national boundaries.

Notes

1 This chapter is rewritten with updates from my previously published chapter, “Chinese: Once Excluded, Now Ascendant” (pp. 37-44 in Eric Lai and Dennis Arguelles, eds., The New Faces of Asian Pacific America. Jointly published by AsianWeek, UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, and the Coalition for Asian Pacific American Community Development). © 2004 Asian American Studies Center Press, reprint by permission.

2 2006 American Community Survey, http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/IPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-geo

id=NBSP&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201&-qr_name=ACS_2006_E

ST_G00_S0201PR&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201T&-qr_name=A

CS_2006_EST_G00_S0201TPR&-reg=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201:035;AC

S_2006_EST_G00_S0201PR:035;ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0201T:035;ACS_2

006_EST_G00_S0201TPR:035&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-_lang=e

n&-format=.

3 43 Chinese were admitted to the United States between 1820 and 1849 according to official immigration statistics. The total number of Chinese immigrants legally admitted into the United State was 424,897 from 1850 to 1959. In contrast, the number admitted was 716,916 between 1960 and 1989, 591,599 between 1990 and 1999, and 460,678 between 2000 and 2006, based on country of last residence (Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2007, table 2, see http://www.dhs.gov/ximgtn/statistics/publications/LPR07.shtm).

4 2006 American community Survey.

5 Chan, This Bitter Sweet Soil; Chan, Asian Americans; Chang, The Chinese in America; Cassel, The Chinese in America; Daniels, Asian American; Glick, Sojourners and Settlers; Hom, Songs of Gold Mountain; Sung, Mountain of Gold; Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore; Valentine, “Chinese Placer Mining in the United States;” Zhou, Chinatown.

6 Aarim-Heriot, Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848-1882; Chan, Asian Americans; Chiu, Chinese Labor in California; Coolidge, Chinese Immigration; Gyory, Closing the Gate; Kung, Chinese in American Life; Liu, The Chinatown Trunk Mystery; McClain, In Search of Equality; Lee, At America's Gates; Miller, The Unwelcome Immigrants; Peffer, If They Don’t Bring Their Women Here; Salyer, Laws Harsh as Tigers; Sandmeyer, The Anti-Chinese Movement in California; Saxton, The Indispensable Enemy; Shah, Contagious Divide; Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore.

7 Chan, This Bitter Sweet Soil; Chan, Asian Americans; Chow, Chasing Their Dreams; Lydon, Chinese Gold; Zhu, A Chinaman’s Chance; Zo, Chinese Emigration into the United States.

8 Chan, This Bitter Sweet Soil; Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 1850-1943; Chow, Chasing Their Dreams; Dicker, The Chinese in San Francisco; Lydon, Chinese Gold; McCunn, An Illustrated History of the Chinese in America; Nee and Nee, Long Time Californ’; Hsu, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home.

9 Chan, Asian Americans; Lee, The Chinese in the United States of America; Lee, The Growth and Decline of Chinese Communities in the Rocky Mountain Region; Lyman, Chinese Americans; Tchen, New York Before Chinatown; Zhang, “The Origin of the Chinese Americanization Movement;” Zhu, A Chinaman’s Chance.

10 Chin, Paper Son; Fry, “Illegal Entry of Orientals into the United States Between 1910 and 1920;” Hsu, “Gold Mountain Dreams and Paper Son Schemes;” Lau, Paper Families; Siu, “The Sojourner;” Wong, American Paper Son.

11 Sung, The Adjustment Experience of Chinese Immigrant Children in New York City; Zhao, Remaking Chinese America.

12 Wong, “Chinese Americans.”

13 Si Yi (Sze Yap) includes four counties—Taishan, Kaiping, Enping, and Xinhui—and the people share a similar local dialect. San Yi (Sam Yap) includes three counties—Nanhai, Panyu, and Xunde, and the Pearl River Delta counties (such as Zhongshan) were among the main sending communities in the Canton region.

14 U.S. Census Bureau, The American Community, Asians.

15 Ibid.

16 Referring to Consolidated Metropolitan Statistics Areas (CMSA) of New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, Los Angeles-Anaheim-Riverside, and San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose. Chapters 3 & 4 in this volume offer a detailed description and analysis of Chinese New York and Chinese Los Angeles.

17 Fan, “Chinese Americans;” Fong, The First Suburban Chinatown; Horton, The Politics of Diversity; Laguerre, The Global Ethnoplolis; Li, From Urban Enclave to Ethnic Suburb; Ling, Chinese St. Louis; Ng, The Taiwanese Americans; Wong, “Monterey Park;” Tseng, Suburban Ethnic Economy; Yang, Post-1965 Immigration to the United States; Zhou, “How Do Places Matter.”

18 Chen, Chinatown No More; Fong, The First Suburban Chinatown; Lin, Reconstructing Chinatown; Zhou, “Chinese;” Zhou and Kim 2003, “A Tale of Two Metropolises.”

|